Fun with Negation

By Jon N. Hall

July 18, 2019

Not, nor, neither, never, no, un-, in-, a-, il-, dis-,

non-, and other means of negation are

things without which thought, as we know it, could not exist.

Please excuse that last

“not,” but I just could not think of a way of not using it. Indeed, it’s

difficult to imagine that there are any earthly languages that do not have at

least one word or prefix that negates. Could we understand an alien race of extraterrestrials

that didn’t use negation? Our minds, mind you, depend, in part, on the ability

to handle negation. Or am I not seeing something? Yet, negation, as with so

many other fundamental and essential features of Mind on this planet, is often

misused and abused. Since so many Earthlings have not entirely mastered it,

let’s look at some forms and aspects of negation, and have some fun.

In Zhouqin Burnikel’s May 8, 2017 crossword puzzle in The New York

Times, “Not good” is the clue for 17-Across. As its answer is “bad,” the

clue is a litotes; i.e. a figure of speech whereby “an affirmative is expressed by negating its opposite.” And with its ironic answer of “oh, fun,” we seem to

also have litotes in

the clue for 8-Down: “That sounds good … NOT.”

NOT, by the way, is the Big Daddy

of negators. Without NOT, we couldn’t get computers to work, as they rely on

the inverter circuit, or NOT gate. In

logic, NOT is an essential connective and a Boolean operator. In English, “not”

is an adverb. Whether in formal logic, or in a computer programming language,

or in a “natural language” like English, the placement of a negator is paramount,

to wit:

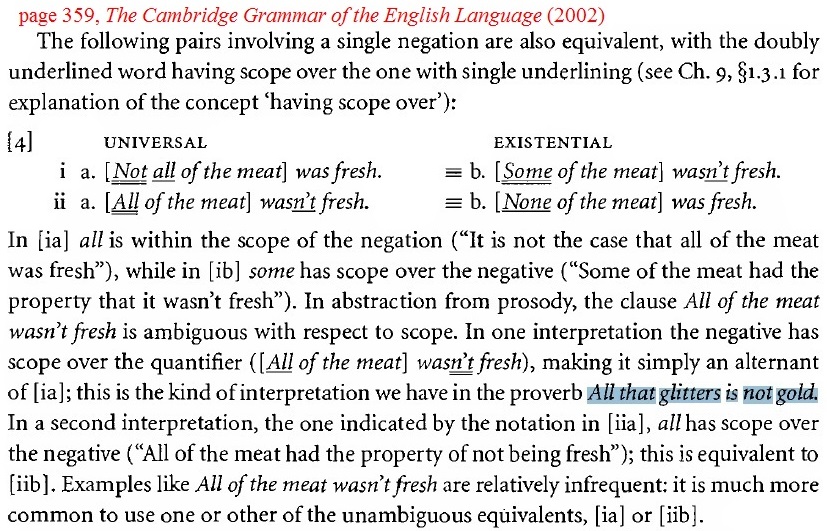

In a May 15, 2017 movie review at Vulture, Kevin Lincoln writes: “If anything’s been made clear

by the preponderance of movies based on preexisting intellectual property, it’s

that all IP is not good IP.” Ponder that last clause. The structure itself can

be valid, e.g.: All IP is not physical property. But what Lincoln is literally

saying is that there’s no such thing as “good IP.” (Tell that to President Xi

and the Chicoms!) Where Mr. Lincoln errs is in his placement of “not.” What he

should have written and surely intended is this: Not all IP is good IP.

I suppose we should ask: Just

what is negation? Negation is contradiction, i.e. denial. Negation is

when we say some specified thing is, uh, not. But negation doesn’t necessarily

indicate what is. Just because something is “not good,” as with the litotes

above, doesn’t mean that it must be bad, it could be average, mediocre.

Mediocre is both not bad and not

good, no? The only way that negation can really indicate what must be is with

true binaries, like on and off. Not on is off, right? There’s the old joke

about being “a little bit pregnant”; you’re either pregnant or you’re not. Not even yes and

no are true binaries, as “maybe” might be the case.

One type of negation is “joint

denial,” which one gets when one uses

NOR. As this article strives to provide something for all tastes, masochists

are advised to read up on the electronic circuit called the “NOR

gate.” And here’s a free book on

negation for your delectation: A Natural

History of Negation by Laurence

R. Horn, so don’t say I never gave you anything. (Whether or not Keats’ negative capability should be included in an article on negation I’ll leave to the

reader.)

One place where folks get

into trouble with negation is “double negatives,” that is, the negation of a

negation. Schoolmarms have advised against the use of double negatives, as

errant use of them can mark one as poorly educated. But sometimes we misuse

double negatives deliberately, such as in “I can’t get no satisfaction” or “I

ain’t got no money, honey” or “ain’t no sunshine when she’s gone.” One can find

such solecisms amusing, endearing, or even soulful.

Double negatives per se are neither

illogical nor uncommon, but when using them, do take care. Parmenides contended

that: “Whatever is, is,

and cannot not be.” There ain’t

nothin’ wrong with that. Perhaps a corollary to Parmenides’ maxim might be:

Whatever is not, is not, and cannot not not be (sic).

But now we’re having too much

fun. My corollary contains a triple negative, which is what Groucho Marx used

when he quipped “I cannot say that I do not disagree

with you.” A better corollary might be: Whatever is not, is not, and

cannot be. Old Parmenides could also have said: Whatever is, is, and must be.

But negating a negative is too cool not to use; it has a certain je ne sais quoi, non?

The intelligences that we’re

busy engineering, Artificial Intelligence, need to have an unambiguous grasp of

negation, unlike their biological creators. And built into their silicon DNA

should be the First Law of Robotics, which as it happens is negative: “A robot may not

injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.”

The rights enumerated in our Bill

of Rights are negative. These negative rights forbid the government from taking

away the unalienable rights endowed by the Creator. The dispute between

conservatives and progressives largely concerns the debate over negative and positive rights.

In Goethe’s Faust, Mephistopheles claims, “I am the spirit that negates.” That serves as the title for an aria in Boito’s Mefistofele: “Son lo spirito che nega.” (Opera

lovers can click here

for commentary on the aria by Neil Kurtzman, and some terrific historical

audios, especially the one of Ghiaurov.)

A regular killjoy, Mephistopheles

says “no” to everything, (except of course to the damnation of Faust, about

which he’s quite keen). Unlike Mephisto, one of the big problems of Modern Man,

especially the American variety, is that we seem to have no ability whatsoever

to say “no.” Folks give in to their every whim and impulse. This inability to

say “no” accounts for much of today’s social pathology.

In David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, Colonel Brighton

tells General Allenby as Damascus falls: “Look, sir, we can't just do nothing.”

Allenby replies: “Why not? It's usually best.” (“Don’t just do something; stand there!”). Elsewhere in the flick, Prince Feisal tells

Lawrence: “I

think you are another of these desert-loving English: Doughty, Stanhope, Gordon

of Khartoum. No Arab loves the desert. We love water and green trees, there is

nothing in the desert. No man needs nothing.”

Oh, but we do need nothing, don’t

we? By confronting Nothing we come to terms with ourselves and with life. We go

into the desert to “find ourselves” by staring into the abyss at Nothing. And

when we emerge from the desert, we are renewed and ready to forge ahead, all

because we dealt with Nothing. I’ll be damned if we don’t need Nothing.

Surely “nothing” is the

ultimate in negation. In Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome,

the Waiting Ones call the desert wasteland created by nuclear war “the nothing.” To get to Bartertown, Max

and a couple of kids must make the perilous trek across the nothing.

It’s been said, “Nothing is,

but thinking makes it so.” Indeed, without thinking, where would nothing be? Perhaps

we invented “nothing” when we thought of what would be the opposite of

everything, i.e. when we negated everything. After that we were able to invent the

number zero. And after that we conceived of negative numbers and nothing’s been

the same since.

But does “nothing” really

exist? I vaguely remember that some physicists have hypothesized that there is

no “nothing,” not even in a vacuum. So unoccupied space may not exist; it may be only a concept, a

product of negation. On the bright side: “When you ain't got nothing, you got

nothing to lose.” But, don’t you also have nothing to lose when you do have “a whole lot of nothing”?

If you have nothing better to

do, you can read Less than

Nothing by Slavoj Žižek. But by no

means should you buy the book, as the author is a Marxist and therefore not in

need of money. Instead, download this free PDF

of the book. And don’t ever say I never gave you less than nothing.

The quintessence of nothing

is surely Nothingness.

In Fellini’s 8½, the film critic tells the director: “If we can’t

have everything, Nothingness is true perfection.” Given the alternatives, most

normal folks would gladly do without perfection and settle for less than

everything.

Heidegger asked: “Why is there something rather than nothing?” I’ve gotta think that’s a fairly big question, and above

my pay grade. Some hold that the spark we think of as Mind is destined for annihilation, i.e. nothing, and

that we ourselves will be utterly negated when we “kick the bucket.” If so, at

that point we won’t be able to have any more fun, not even with negation. So until

you suffer total negation, quit being so negative and have some fun.

Comments

Post a Comment