British Linguists Mangle Logic

By Jon N. Hall

September 30, 2019

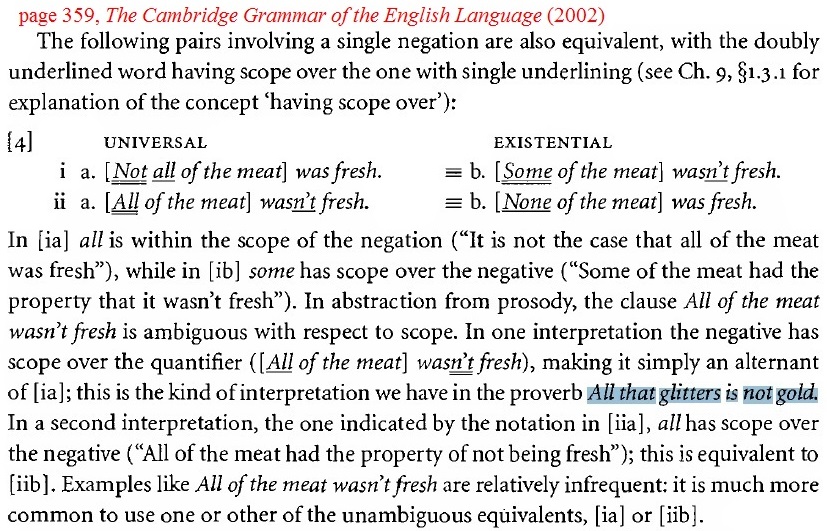

The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (2002) is a 1,842-page

tome by Rodney Huddleston, Geoffrey K. Pullum, and thirteen other contributors.

At the Cambridge University Press, the CGEL is touted as the

“definitive grammar for the new millennium.”

Well,

a thousand years is a mighty long time,

but at $324 one would hope that the claim

would prove true for at least the beginning of the new millennium. So let’s see

whether or not this descriptivist grammar can shed some light on a narrow issue

that concerns conjunctions. (Forgive me if I anthropomorphize CGEL.)

“Coordinator” is the term the

CGEL uses for conjunctions, words like “and” and “or.” Chapter 15, “Coordination

and supplementation,” is by linguists Rodney Huddleston, John Payne, and Peter

Peterson. In section “2.2.2 And and or in combination with negation” on pages 1298-9

(or see screengrab below), we are assured that the following two statements are

equivalents:

I didn't like his mother or his father.

I didn't like his mother and I didn't like his

father.

That suggests that the CGEL

thinks the first statement cannot be interpreted as written, that is, as

containing a disjunction of negations. Rather, the CGEL thinks its first

statement must be interpreted as though it contained a conjunction of negations, whereby “or” is interpreted as “and.”

One little problem for the

CGEL is that a disjunction of negations is perfectly grammatical and perfectly

logical. Ergo, the first statement can be interpreted literally. Yes, it would

be a strange kind of statement if it were interpreted as a disjunction of

negations, leaving those who hear it to wonder which of the two wasn’t liked.

But it’s not much stranger than if negation had been left out of the statement:

I liked

his mother or his father.

Passing strange, no? In that

disjunctive affirmation, the strangeness is salient, and folks might ask: Don’t

you know which of his parents you liked? But if negation is added, the oddness

is masked, and it allows folks to supply the meaning that they think is

intended. So, if a disjunction of negations is grammatical and logical, how

does the CGEL propose that one express that in, you know, English?

Although there are numerous

mentions of ambiguity in the CGEL, there are none in Chapter 15’s section

2.2.2. Yet, they do remark that their examples provide for “natural”

interpretations as well as for those that are “less salient.” But nowhere does

the CGEL allow that their first example can be read literally, as a

disjunction, where “or” is “or.” So consider this:

It was baffling; I knew that I didn't like his

mother OR his father, but I couldn’t tell which one I disliked because

they were always together. I sensed that if I could interact with each of them

separately that I might well have liked one of them. But then, had I gotten to

know each separately, I might have discovered that I didn’t like his mother AND I didn’t

like his father.

One type of disjunction of

negations that normal folks wouldn’t interpret as a conjunction is when the

disjuncts mutually exclude each other, such as in the “off” and “on” of this: The switch is not off or on. Folks would

rebel if linguists told them that this meant: The switch is not off AND the

switch is not on. But that’s the sort of thing that the CGEL is doing in their

first example. Incidentally, my example here has the same meaning as: The switch is on or off.

A disjunction of negations

may work best with the “exclusive or,”

which the example of the switch certainly is. In any event, statements like the

CGEL’s first example should be avoided -- only hardcore logicians should be

allowed to use disjunctions of negations.

If, in the example “I didn't like his mother or his

father,” “or” must be interpreted as “and,” then one might assume that the

CGEL is invoking De Morgan’s laws of formal

logic. That might also be assumed because just to the right of the CGEL’s example

appears this: “not A-or-B” = “not-A and not-B.” That’s a Morganian equation,

and it would lead one to conclude that the CGEL thinks the first statement is

actually a negation of a disjunction rather than a disjunction of negations.

However, at the bottom of the page we’re given this example:

I didn't like his mother and father. [Emphasis

added.]

In keeping with the logic of

their first example, one might expect that the “and” in this last example would

be transformed into “or.” But no, as we learn on the next page, it will most

likely be interpreted as written, i.e. as “and.” Thus, according to the CGEL

this last statement can be interpreted exactly

like their first statement! But the two are structurally the same, and

there are no notations, such as the parentheses required by De Morgan, to

signal that the CGEL’s first statement works differently than this last

statement. But De Morgan’s laws are “reciprocal”; they apply to both

disjunction and conjunction. Even so,

throughout section 2.2.2, De Morgan’s laws seem to be applied inconsistently.

Linguistics is supposed to be

a science. But it shouldn’t take much science to find out how the majority of

Anglophones interpret the CGEL’s examples. What would require a bit of science

is to demonstrate that the wiring of the brain accounts for the alleged

Morganian transformation of their first example.

It’s doubtful that your

average Anglophone is aware that he might be performing any kind of

transformation when he takes in statements like the CGEL’s first example. It’s

doubly doubtful that many Anglophones have even heard of De Morgan, so his laws

probably have nothing to do with the way we interpret disjunction under

negation -- unless the human brain is Morganian. But again, if the human brain is indeed Morganian,

then what about the second example, where transformation doesn’t happen?

In the less than two pages

that section 2.2.2 takes up, De Morgan’s equations are trotted out twice. If

the CGEL does think that De Morgan’s laws do obtain, then it is bad form that

they don’t cite the logician; they drag out his equations and then don’t

mention him. Incidentally, a truer way to represent De Morgan’s laws than the

CGEL’s is to use parentheses: NOT (A OR B) = (NOT A) AND (NOT B).

The culprit in all this seems

to be the CGEL’s misunderstanding of “scope,” something they refer to 13 times in the short

section. Indeed, section 2.2.2 begins with an assertion about scope that they

apply to their first example, referring to statements in which an “or-coordination” [mother or

father] falls within the scope of a negative.” However, in their second example

(mother and father) the CGEL contends that “and” has scope over the

negative. In other words, in their first example NOT has scope over OR, but in

their second example AND has scope over NOT. Nonsense, both examples have the

same structure.

Scope is better understood by

mathematicians and by logicians than by linguists. De Morgan’s laws give NOT

scope over both disjunction and conjunction through the distributive property, which is accomplished by the use of parentheses. But

again, we have no such notation in the CGEL’s examples herein. And, if “and” were

to have scope over the negative, then what has scope over the conjuncts

“mother” and “father,” eh? (The CGEL may have succeeded in creating an entire

new solecism; call it the “dangling conjunct.”)

The reason the CGEL devised a

theory about “and” having scope over the negative is to preserve the Morganian

theory they devised for “or” under negation. You see, if De Morgan obtained for

both, OR would always be read as AND, while AND would always be read as OR, and

madness would reign. De Morgan has nothing to do with it, or so I contend.

If an “or-coordination” under negation seems odd, one “quick and dirty”

rewrite is to just change the “or” to “nor”: I didn't like his mother nor

his father. Your word processing program might flag that “nor” but ignore

it; grammar-check programs are by no means infallible. Another solution: I liked neither

of his parents.

Those rewrites, however, may

be a wee bit too “prescriptive” for the CGEL crew. You see, the authors of the

CGEL cleave to descriptivism,

and what seems quite beyond the abilities of descriptivists is the recognition

that some of the examples provided in section 2.2.2 are simply “bad English.”

The idea that there is such a thing as bad English is one that descriptivists don’t

seem to want to entertain.

This business with “or”

brings out the latent prescriptivist in me. However, prescriptivists are of little help

here. Indeed, on this matter, prescriptivists might as well be descriptivists. On

the issue of “or” under negation, the entire language industry is deficient:

the prescriptivists tell us to avoid

“nor” and instead use “or,” and then the descriptivists

condone “or” being interpreted as “and.” C’mon, boys, let’s get some

“coordination” going.

Comments

Post a Comment