H.W. Fowler and the History of

an Error

By Jon N. Hall

October 7, 2019

For the last century or so, language

experts have been having a hard time with the conjunction “nor.” For example, in

his entry for NOR in The Penguin

Dictionary of American English Usage and Style (2000), Paul W. Lovinger

considers a perfectly grammatical construction, which he even admits “some

grammarians would condone,” but still advises: “Change ‘nor’ to or.”

What, pray, is wrong with

“nor”? Lovinger never really explains. But he might try to understand how “nor”

and “or” actually function and what they specify, for he also writes: “Nor, like or, links alternatives.”

Not so. The word “alternative”

indicates choice. “Nor,” however, does not link choices; it links things which

are all excluded, denied, disallowed,

or negated. In the online Oxford English

Dictionary, the fourth selection in the entry for NOR has this quote by W.

E. Gladstone: “Not a vessel, nor a gun, nor a man, were on the ground to

prevent their landing.” Are we to think that a gun or a man could have been on the ground? Of course

not; both gun and man were kept from being on the ground by little old “nor.”

Parents who tell their spirited daughter that she cannot date Tom, Dick, nor Harry, aren’t offering her an

alternative.

The confusion surrounding “nor”

seems to be of recent vintage. Shakespeare certainly understood the word when

he penned: “Not

marble, nor the gilded monuments / Of princes, shall outlive this powerful

rhyme.” (No one’s gonna correct the Bard, are they?)

Shelley also exhibited a knack

for “nor” when he wrote: “NOR

happiness, nor majesty, nor fame, / Nor peace, nor strength, nor skill in arms

or arts, / Shepherd those herds whom tyranny makes tame.”

As late as 1954, the American

novelist Alan Le May showed that he could correctly handle “nor” in The Searchers: “You don’t have to call

me ‘Sir,’ neither. Nor ‘Grampaw,’ neither.

Nor ‘Methuselah,’ neither. I can whup you to a frazzle.”

By 2013, however, in Edna

O’Brien’s Country Girl: A Memoir we

read that as a schoolgirl she had been disappointed that Jesus “had been so curt with his mother at the Feast of

Cana, when, worried about the scarcity of wine, he said, ‘It is not my business

or thine.’” (Surely Jesus would have used “nor.”)

Here’s the Culprit

In 1926, the revered British

usage maven H.W. Fowler became the genesis of our bad usage with his venerated A Dictionary

of Modern English Usage. In the

first paragraph of his entry for NOR, Fowler posits that “He does not move or speak” is

the equivalent of “He neither moves nor speaks.” Fowler then explains:

The tendency to

go wrong is probably due to confusion between the simple verbs (moves &c.)

& the resolved ones (does move &c.) ; if the verb is resolved,

there is often an auxiliary that serves both clauses, &, as the negative is

attached to the auxiliary, its force is carried on together with that of the

auxiliary & no fresh negative is wanted.

Gobbledygook! Mr. Fowler contends that negative force “is carried on” by means of an auxiliary. But the English language

doesn’t need auxiliaries to carry negative force onward. Language is linear; it

has only one place to go, and that’s onward. The subject goes forth into the

predicate; that’s the way language usually works. So the business about “this carrying

on of the negative force” is a mite daft. Of course, it carries on. Meanings coalesce

as one moves onward, piling up words.

What “He neither moves nor

speaks” really imparts is: He does not move and

he does not speak. And if that be so, then Fowler and I have expressed the same

sense with three conflicting conjunctions. But that’s not the case, because one

correct reading of Fowler’s “He does not move or speak” is: He does not move or he does not speak. And that isn’t

equivalent.

With his fixation on

auxiliaries and “resolved verbs,” Fowler shows that he does not fully understand

conjunctions. For it is not the leading negative that does the work here; it is

the conjunction. Indeed, “nor” doesn’t even need a leading negative. However,

Fowler seems to think such usage “is legitimate in poetry,” but not in

“ordinary” prose. Although it is now less common, one can still hear this usage

of “nor.” For example, in her dispatch

from Moscow on February 19, 2014, Fox News correspondent Amy Kellogg said this:

“Ukraine desperately needs money, which Moscow, uh, nor anyone would be likely to dispense to a government that does

not have control of the country, Bret.”

Fowler offers up several

erroneous examples that he attempts to fix. In five of the examples he says

that “or must be corrected into nor if the rest of the sentence

is to remain as it is,” which is terrific. But Fowler’s disdain for “nor” is so

strong that he then goes on to rewrite the examples so that he doesn’t have to

use the dread word, and in those rewrites he makes a mess of things. What’s

disturbing is that this madness has been sanctioned by language experts on both

sides of the Atlantic for at least the last 93 years!

Not everything Fowler wrote

about “nor” is nonsense. But if I were Fowler’s editor, I’d advise him not to

begin an entry with the Book of Common Prayer unless it is free of sin. This is not the case with

his entry for NOR.

The

Error Proliferates

Fowler’s tome was first revised in 1965 by Sir Ernest Gowers, (download the PDF of the book and go

to page 394 for his entry on NOR). In

this second edition, Sir Ernest inserts his own example and corrects it, and

it’s fairly interesting:

In this kind of work there was often little oral preparation of material,

little systematic collection of facts and views, well assimilated and digested,

or much discussion of balance and proportion. The writer has forgotten that he began there was

often little and has ended as though he had said there was seldom much.

Or must be corrected to nor was there.

Sir Ernest makes a serious

mistake here, as he fails to recognize that his example does not contain a negative and therefore

cannot be used to illustrate the problem. “Little” is attenuation, not negation. He then compounds that

mistake with his correction; replacing “or” with “nor was there” would negate the

previous items. But as Sir Ernest noted, the author of the example created the

problem with his shift from “little” to “much.” What he (probably) intended would

be better said by continuing with the parallelism; that is, by changing “or

much” to “and little.”

The snag with that rewrite is

that I’m assuming I know what the author intended. But perhaps the author meant

exactly what he wrote. After all, his statement is grammatical, and can be read literally, as presenting three alternatives;

i.e. little oral preparation, little systematic collection, or much discussion.

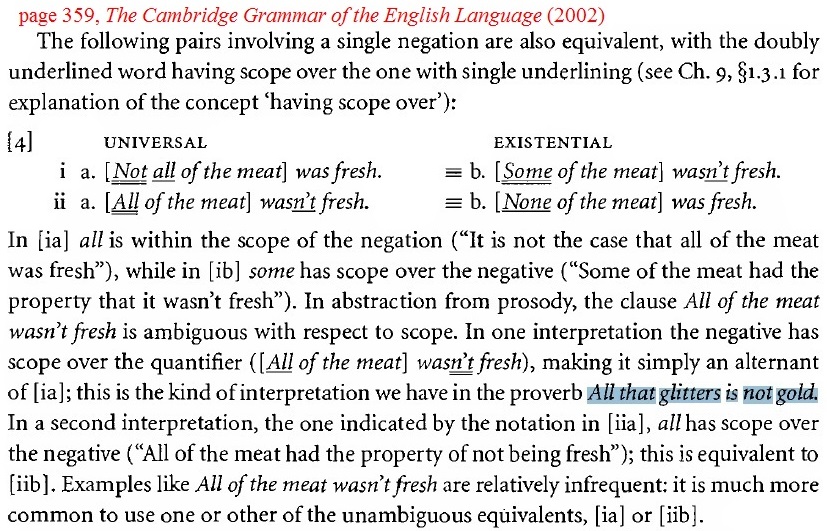

Inasmuch as Sir Ernest

deletes some of the first edition’s examples, if you want to read all of them

refer to the screengrab below of Fowler’s entire entry for NOR. And if you’re interested

in what the enskied and sainted H.W. Fowler had to say on other

issues of usage, refer to “The Classic First Edition.” British language

expert David Crystal provided added notes in the section “Notes on the Entries,”

but, alas, there is no note on “nor.”

In 1996, R.W. Burchfield revised Fowler (download the PDF of the book and go

to page 527 for his entry on NOR). Mr. Burchfield wisely (and mercifully)

avoids our issue altogether. In fact, the third edition seems to have replaced

Fowler’s entry in its entirety. Good show, old boy.

In 2015, Jeremy Butterfield revised Fowler with a fourth edition, and retained some of Burchfield’s

sensible positions on “nor” from the third edition. Even

so, the damage had already been done, as Fowler’s crazy ideas about

conjunctions had continued to proliferate among prescriptivists, including the

respected American usage expert Bryan A. Garner, who seems to be channeling

Fowler when he writes that the “initial negative carries

through.”

In any case, the rules of the

English language have got to provide for those arenas where expression must be

100 percent unambiguous. If you can’t devise such rules, step aside.

If that sounds like the

ravings of some pathetic anal retentive stickler, some grammar Nazi, then know

that I don’t mind it so very much when regular folks misuse the language. In

fact, I mydamnself just love to mangle the frickin language; I often write my

emails in the patois of an Ozark hick, which for me comes natural. It’s when the

experts, the “Rule Makers,” mess up that this kid gets riled. Language experts,

I can whup y’all to a frazzle.

Comments

Post a Comment