All that Glitters Is Not

What?

By Jon N. Hall

January 10, 2020

The literal takeaway from the old adage

“All that glitters is not

gold” is

that gold doesn’t glitter. In case you don’t know, that’s false, gold does in

fact glitter. So we’re told that what the adage really means is this – Not all that glitters is gold.

In the original form of our

adage, “not” modifies “gold.” Therefore, “not” has scope over “gold.” In linguistics, a word’s scope is the

part of a statement over which it operates. Some linguists contend that in our

adage “not” can also have scope over “All.” This is the position taken by what

may be the ne

plus ultra of descriptivist grammars, The Cambridge Grammar of

the English Language.

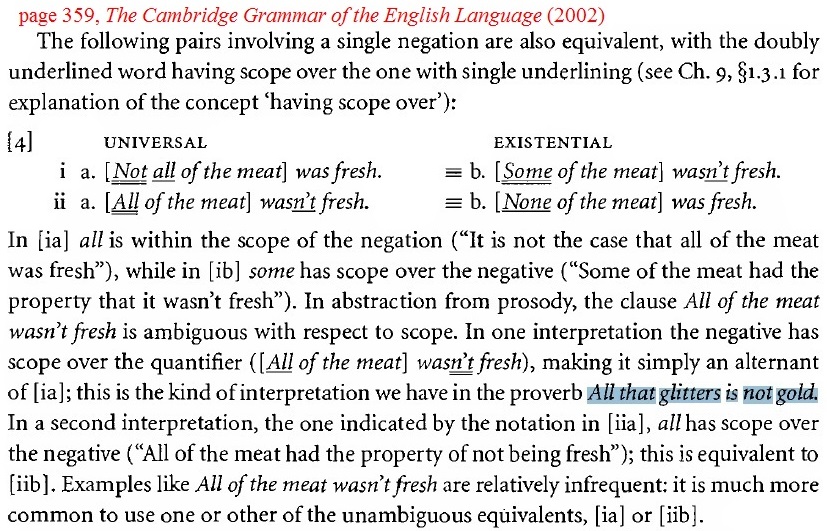

The

one reference in the CGEL to our adage is in

the middle of page 359 (screengrab below), where the CGEL contends that “All

of the meat wasn’t fresh” is akin to our gold adage in that it “is ambiguous

with respect to scope. In one interpretation the negative has scope over the

quantifier […] this is the kind of interpretation we have in the proverb All that glitters is not gold.”

But unlike our gold adage,

the CGEL’s example isn’t absurd when taken literally, for it could be the case

that all of the meat was rancid, i.e.

not fresh. Even so, the CGEL contends

that it can be interpreted in the same manner, as though “not” were at the

start of the statement thus: “Not all

of the meat was fresh.” To illustrate the problem with the CGEL’s position on

this, let’s consider our adage with a substitute predicate that is not

problematic – All that glitters is not dull.

That’s “dull,” as in

non-glittery. Now, this new statement might be tautological and it doesn’t tell

us much, but it does have the virtue of being unambiguous. And the point is, by

merely substituting “gold” with another word we can see that “not” clearly

modifies that other word, and does not modify nor have scope over “All.” If descriptivist linguists think that it

is legitimate to interpret our gold adage by (mentally) repositioning “not” to

the start of the statement, then it should also be legit to interpret “All that

glitters is not dull” as – Not all

that glitters is dull.

But such an interpretation

takes us quite beyond mere falsity and into the realm of insanity. It would

seem that the “legitimacy” of such interpretations is dependent on the

“literal” interpretations being false, which is why the CGEL’s example of “All

the meat wasn’t fresh” doesn’t work; it’s not an absurd statement.

Language maven Lane Greene writes me that my “concocted example (‘All that

glitters is not dull’) doesn't prove anything because you’ve forced the choice

by making the CGEL interpretation semantically impossible.” But that might also

be said about our adage, it “forces” an interpretation by asserting a

falsehood.

Also on page 359 of the CGEL,

we read “see Ch. 9, §1.3.1 for explanation of the concept ‘having scope over’,”

which starts on page 790.

This writer is not buying the CGEL’S understanding of scope, as it seems at

odds with how scope is treated in logic and mathematics. In those two

disciplines, scope is quite tidy, and

it is a function of position and notation (see this useful Usage Note). But there’s little

of that in the examples that the CGEL trots out. So the question becomes: Do the

CGEL’s descriptivist linguists really understand scope?

We find evidence that this

may be the case at the bottom of page 1298 in the CGEL, where it is alleged that in “I didn't like his mother and father,”

the conjunction “and” has scope over the negative. The reason for such a

position may be because to say otherwise would conflict with the Morganian

theory the CGEL floats on the same page (see “British Linguists Mangle Logic.”) It seems that descriptivist linguists may have some

indefensible positions on scope.

In section “1.3 Matters of scope” of Laurence R. Horn’s entry “Negation” in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, there is a single iteration of

our adage:

Despite the locus classicus All that glitters is

not gold and similar examples in French, German, and other languages,

the wide scope of negation over universal subjects (or in cases like All

the boys didn’t leave, the possibility of such readings, depending on the

speaker, the intonation contour, and the context of utterance) is often

condemned by purists, yet is not as illogical as it may appear (Horn 1989, §3.4).

The reference is to Horn’s 1989

book A Natural

History of Negation, where on

page 226 (go to 270 in the PDF) he begins a chapter devoted to our adage and

related matters: “4.3 All that Glitters:

Universals and the Scope of Negation”:

Jespersen cites a wide range of attested examples, dating back to Chaucer,

where negation takes wide scope over a preceding universal, so that all … not must be read as not all.

Now, there is such a thing as

“wide scope” and it can cause ambiguity, here’s an example: He was pelted with rabid bat guano. So,

is the bat rabid or is the guano rabid? Does “rabid” have scope over just “bat”

or over “bat guano”? If its guano were rabid, one would assume that the bat

would also be rabid. But I read that one cannot get rabies from bat guano, so

it must be the guano of a rabid bat. One quick fix for the ambiguity here might

be a dash: rabid-bat guano.

Do notice that in our guano

example, the wide scope is linear, and goes forward. But the wide scope alleged

by our linguist friends in their examples is rather different; rather than

modifying what follows, it modifies what came before. That reminds me of the running gag in Wayne’s

World where irony (or something)

was expressed by merely adding a “not” to the end of a statement: “Wow! What a

totally amazing, excellent discovery … NOT!” and “I'm having a good time … NOT!”

and “Wayne will understand that right away … NOT!” In Wayne’s world, our adage

would be expressed thus – All that glitters is gold … NOT!

I suppose the gag was funny

at the time (25-30 years ago), but does it shed any light on the “retrograde scope”

that linguists allege “not” has in our adage? Well, consider the scope that a

preposition positioned at the end of a sentence has; it would seem to be

retrograde. The CGEL treats such preposition positioning in section “4.1

Preposition stranding: What was she

referring to?” on page 626. I’d

say their “to” has retrograde scope over “What,” but what do I know?

In Scope

Fallacy, Gary N. Curtis has a

slightly different idea of wide

scope than descriptivist linguists,

as he maintains that in our adage “not” negates not just “All,” as the CGEL and

Horn say, but the entire rest of the sentence. Regardless, their interpretation,

“Not all that glitters is gold,” also

has problems. They may contend that “Not all” has the implicature of “some,” but it

can also be read as “none.” Let me remind you: “some” and “none” aren’t

equivalent.

So it seems the experts may have

substituted one ambiguity with another ambiguity. Not good. One way to get a better

bead on the scope issue here is to delete the negation in our adage like so –

All that glitters is gold.

Now, most sentient carbon-based life forms will know that this change

created yet another false statement. E.g., iron pyrite (fool’s gold) glitters

and it’s not gold. The commercial product glitter glitters and it’s also not

gold. By the way, has anyone been

asserting that all that glitters is gold? No sane persons that this kid’s

aware of. So if no one is saying that, then why negate it? And why then defend

the introduction of negation into a statement that no one’s making?

When shorn of its negation, we

see that the problem with our gold adage is more than scope. You see, our adage

takes the form of a generalization, when the intent is just the opposite, a

“particularization.” We’re taught that generalizations should be made with

care, and even avoided. We can do that with our adage with a simple

substitution that attenuates – Much

that glitters is not gold.

The virtue of such an

interpretation, where “All” becomes “Much,” is that it would create a fairly

unambiguous statement. Also, it leaves “not” in situ, i.e. in place. That seems less of an alteration than

changing what is being negated, which involves mentally restructuring the

statement.

Scope qua scope doesn’t exist out there in Nature, does it? It’s simply a

concept, which math, logic, and language analysts use to help them make sense

of things. My concern here is not with how regular folks interpret our adage.

Rather, my beef is with the linguists’ explanations for that interpretation,

which is all bound up in their particular position on wide (retrograde) scope.

As with all of the “social sciences,” one must wonder if they’re just making

stuff up.

Again, Laurence Horn asserts

that: “all … not must be read as not all.” But why “must” these statements

be read that way? Why can’t they be read literally and regarded simply as

mistakes? After all, mistakes are not so awful; we all make them. Even so, the

language experts would seem to have us believe that this statement is perfectly

fine – All that seems crazy is not illogical.

If that seems unambiguously and

irredeemably crazy to you, then to extend a little charity to

your interlocutor you might interpret it like this – Some of what seems crazy is not illogical.

What actually takes place in

folks’ minds when they hear our gold adage in its original form? Do we

reposition/transpose negation by using wide scope like some language experts contend,

where “All … not” becomes “Not all”? Or do we attenuate, where “All” becomes “Much”

or “Some”? We might need a neurologist to get a definitive answer. But

regardless of what we’re doing, we’re doing it to make sense out of nonsense.

Comments

Post a Comment